Background

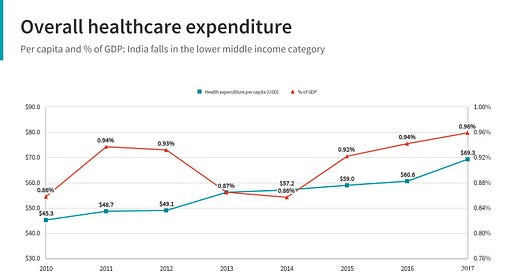

In the last decade, India has made gains in controlling diseases, such as polio, and improving access to maternal (maternal mortality ratio or MMR has dropped from 556 deaths per 100,000 live births to below 130), child health, and family planning services. On aggregate, however, India’s health system has achieved limited impact on population health outcomes, compared with its peers, and is unable to control high out of pocket payments that comprise 65-70% of total health expenditure.

Note: Maternal mortality is considered a key health indicator and the direct causes of maternal deaths are well known and largely preventable and treatable.

Aging populations give rise to increased non-communicable diseases (NCDs), multi-morbidities, and chronicity. This has necessitated a reorientation of services, such that the provision of care is proactive rather than reactive, comprehensive and continuous rather than episodic and disease-specific, and founded on lasting patient-provider relationships rather than incidental, provider-led care.

While the components contributing to this state of health are multidimensional and vary by context, certain common trends prevail:

Variable and poor quality of services.

Weak regulation and enforcement of standards.

Fragmentation of care within government programs and between the pubic and private sectors (including primary, secondary, tertiary levels), which results in duplication of resources and skills.

Weak governance and accountability structures, with limited evidence-based decision making, or the means to reward and sanction behavior based on performance.

Note: India has a tiered healthcare system with the Service centers (SC) at the bottom, followed by Primary Healthcare centers (PHC), Community Health Centers (CHC,) and finally the District Hospitals (DH) at a rural and peri-urban setting.

There is growing recognition that India’s healthcare system requires targeted reforms to improve the efficiency, quality, and equity of care.

Efficiency means reducing wastage or using resources effectively to satisfy people’s needs and desires. It encompasses 3 components:

Allocative efficiency: benefit attributable to the reorganization of the inputs (allocative efficiency = maximizing total economic welfare; market price = marginal cost of supply).

Technical efficiency: technical relationship of the inputs with the outputs.

X-efficiency: may be described, in crude terms, as the residual portion of efficiency not explained by the above two forms.

Quality is about improving the desired health outcomes. To achieve this, healthcare must be:

Safe: minimizing risks and harm to service users, including avoiding preventable injuries and reducing medical errors.

Effective: providing services based on scientific knowledge and evidence-based guidelines.

Timely: reducing delays in providing and receiving healthcare.

People-centred: taking into account the preferences and aspirations of individual service users and the culture of their community.

Equitable distribution is providing universal access to health services irrespective of ability to pay. An equitable healthcare service must serve high-risk groups like women, children, and underprivileged segments. In India, health services are concentrated in urban areas. In urban areas, slums don’t have similar access to health services.

For efficient & effective delivery of services, an efficient public-health workforce is key. India has one of the lowest density of health workforce; with a density of physicians (7 per 10,000) and nurses (17.1 per 10,000) vs the global average of 13.9 and 28.6 respectively. The nurses-to-physicians ratio in India is about 0.6:1, as against the nurses-to-physicians ratio of 3:1 in some of the developed countries. The issue is very serious, particularly in rural areas, as most doctors and hospital beds are concentrated in urban areas catering to only 20% of India's population.

The need to strengthen primary care as the backbone of the system features importantly in the current climate. Elements of primary healthcare are:

Education concerning prevailing health problems and methods of preventing and controlling them.

Promotion of food supply and nutrition.

An adequate supply of safe water and basic sanitation.

Maternal and child healthcare, including family planning.

Immunization against major infectious diseases.

Prevention and control of locally endemic diseases.

Appropriate treatment of common diseases and injuries.

Provision of essential drugs.

The Draft National Health Policy 2015 acknowledges that government-funded primary healthcare in India is selective and only covers 20% of the population’s primary healthcare needs. As a response, the Central Government has set aside funding for states to experiment with primary care pilot programs, known as Health and Wellness Centers, that will offer opportunities for learning and scale-up towards universal health coverage. A growing number of states, including Kerala and Karnataka, are also implementing broader reforms in primary care to strengthen their health systems, including improving the quality of data for decision making, motivating health workers with training and team-based care models, and incorporating standard clinical protocols.

Reversing the trend of declining support of primary healthcare

The proportion of the Union health budget allocated for the National Health Mission focused on supporting primary and secondary healthcare was reduced to 49% in FY21 from 56% in FY19. We need at least 70% of all health budgets earmarked for this less glamorous but vitally important frontline level of care.

Framework for integrated health services

Alongside the government, the private sector plays an important, and in many locations, a more prominent role to address the primary health needs of the population. This is an extremely heterogeneous and fragmented sector, characterized by different cadres of health professionals, degrees of business formality, capitalization and scale, quality of care, and other factors. There are numerous examples of private providers bringing important innovations to the sector; for example, in launching new medical devices and information technology, efficiently building health worker skills, and creating high volume, low-cost delivery models for different services and population segments. However, many of these models are yet to realize scale or be adequately leveraged by the public health system towards ensuring equitable access to care.

It is increasingly clear that neither the public nor the private sector alone can achieve the goal of universal health coverage; it is time to harness the comparative strengths and resources of both sectors to achieve a basic common denominator of ensuring access to high-quality primary healthcare for the population.

Below are three broad guidelines to shift primary healthcare delivery from fragmented, silos of care to an integrated systems approach.

Focus on assuring primary healthcare that is comprehensive in scope, proactive in design and pro-poor in reach

India has a hospital-centric health system that is designed to treat the sick rather than keep people healthy. It is an expensive system to sustain for both the government and the consumer, depending on who pays. Evaluations of government-sponsored insurance schemes have shown that many cases resulting in hospitalization can be managed at the primary care level, which would result in cost savings to the system. Shifting care closer to the community, organizing it around people’s needs and expectations, and making it patient-centric by developing a relationship with them via early communication, can result in early and rational care-seeking, improve health outcomes, and reduce costs for the government and individuals.

Duplication of resources through current vertical disease programs signals an opportunity to move towards broad-based population health management. This entails a shift away from existing silos (for example, in maternal health) to include non-communicable disease management, mental health screening, and support, improved nutrition, and access to clean water and sanitation. An effective primary health-centered model will focus on active health promotion and prevention, disease management, and coordination between primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of care. It will also ensure that drugs and diagnostics are included in care packages and managed by providers, thus reducing out of pocket expenditures.

Strengthening accountability and performance

A key challenge today is the context and culture of the healthcare system. The places with the greatest needs have the poorest governance and administrative systems. There is substantial evidence on absenteeism and systemic corruption in the healthcare sector, both public and private. More funds to a dysfunctional system can further fuel rent-seeking rather than assure health outcomes. Creating a performance-oriented culture with professionalism and accountability is the greatest challenge and opportunity. Below are two sets of recommendations to improve performance accountability.

The first is to separate the functions of governance, monitoring, and provisioning of care, and to ensure a professional focus to each. At the governance level, it entails creating an autonomous unit that can provide stewardship, oversight, financing, and overall execution of the health system. This includes contracting with private and public providers and ensuring that they are effectively regulated. The governance function should be armed with systems to verify performance and robust information technology to enable data-driven decision-making. Governing units should also include representation by relevant ministries, independent technical experts, and the community.

An independent performance monitoring unit would serve as the eyes and ears on the ground, directly supporting the governance function. This unit will review administrative and financial data, conduct medical audits, collect patient feedback, and verify all aspects of system performance.

The provisioning of care would be contracted to a professional agency, public or private. These entities should be paid on a per capita basis with performance incentives, effectively shifting from input to outcome-based financing. The emphasis must be on the management of population health outcomes. A capitation based model can ensure early and appropriate diagnosis and treatment by providers, and effective care coordination and referrals. Payments to this agency can be based on predefined population-level outcomes, including efficient management of resources and patient satisfaction. In Turkey, for example, family physicians are paid a greater capitation amount for pregnant women and children under five, thus encouraging outreach to this population; they are also liable for a deduction if they do not meet defined maternal and child health targets.

The second solution is to create a Family Health Team structure that comprises different health professionals who are the first point of contact for the community. Such teams are often a core part of the response strategy in countries that have embarked on primary healthcare reforms, such as Brazil and Turkey.

In India, it is proposed that a professional agency (discussed above) manage these teams, ensuring that they have the optimal composition and skills to meet defined standards and deliver quality services.

The Family Health Teams should be accountable for active registration and screening of a defined population, and for improving health outcomes. The teams can comprise public and /or private health workers, depending on the context and existing supply. For example, it should include frontline health workers whom the community already knows and trusts, as well as nurses, paramedical staff, and medical doctors. The teams should be enabled with information technology, including shared electronic medical records, to ensure effective coordination of patient care and accountability. The teams should be motivated by financial and non-financial rewards to ensure performance and a focus on outcomes.

A shift towards integrated delivery between primary, secondary and tertiary levels of care

The integration of primary with secondary and tertiary levels of care is needed to reduce system costs and improve population health outcomes. This integration should entail seamless navigation of citizens through different levels of care. On the provider side, it can entail common protocols for care management and referral, integration of patient health records, and management information systems. Most importantly, it will require alignment of provider payments and performance outcomes (focused on capitation rather than a fee for service), thus ensuring that it is in the financial interest of all providers to keep people healthy. Typically, countries that embark on universal healthcare reforms begin by consolidating different programs and risk pools to ensure that resources are effectively distributed between primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of care.

Final thoughts: learning from the Covid-19 pandemic

The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has exposed the fault lines in our healthcare system and should act as an accelerator in implementing several healthcare reforms (just like in education, commerce). Depending on tertiary hospitals for testing and treatment increases the risk of infection and puts a strain on the public health system. Investment in primary care is needed to manage the pandemic.

Nearly 80%-90% of critical Covid-19 cases are currently being treated by public health services.

States with more robust public health systems like Kerala have been far more successful in containing Covid-19, compared to richer states like Maharashtra and Gujarat, which have under-staffed public health systems.

If you liked reading this newsletter, please spread some ♥️ by sharing this with your friends. For any feedback, please write to me at @manchandarohit.