Swiggy is an online food ordering and delivery platform. By virtue of steamrolling the food delivery logistics in India, it has managed to capture the eye of users, founders, and VCs alike. It was quick to achieve the unicorn status and is currently valued at $3.6 billion. It has managed to create a buzz around itself but the question is — how much is hype and how much is real?

Here’s a snapshot describing the duopolistic food delivery landscape in India:

Let’s jump right in.

What’s driving the demand?

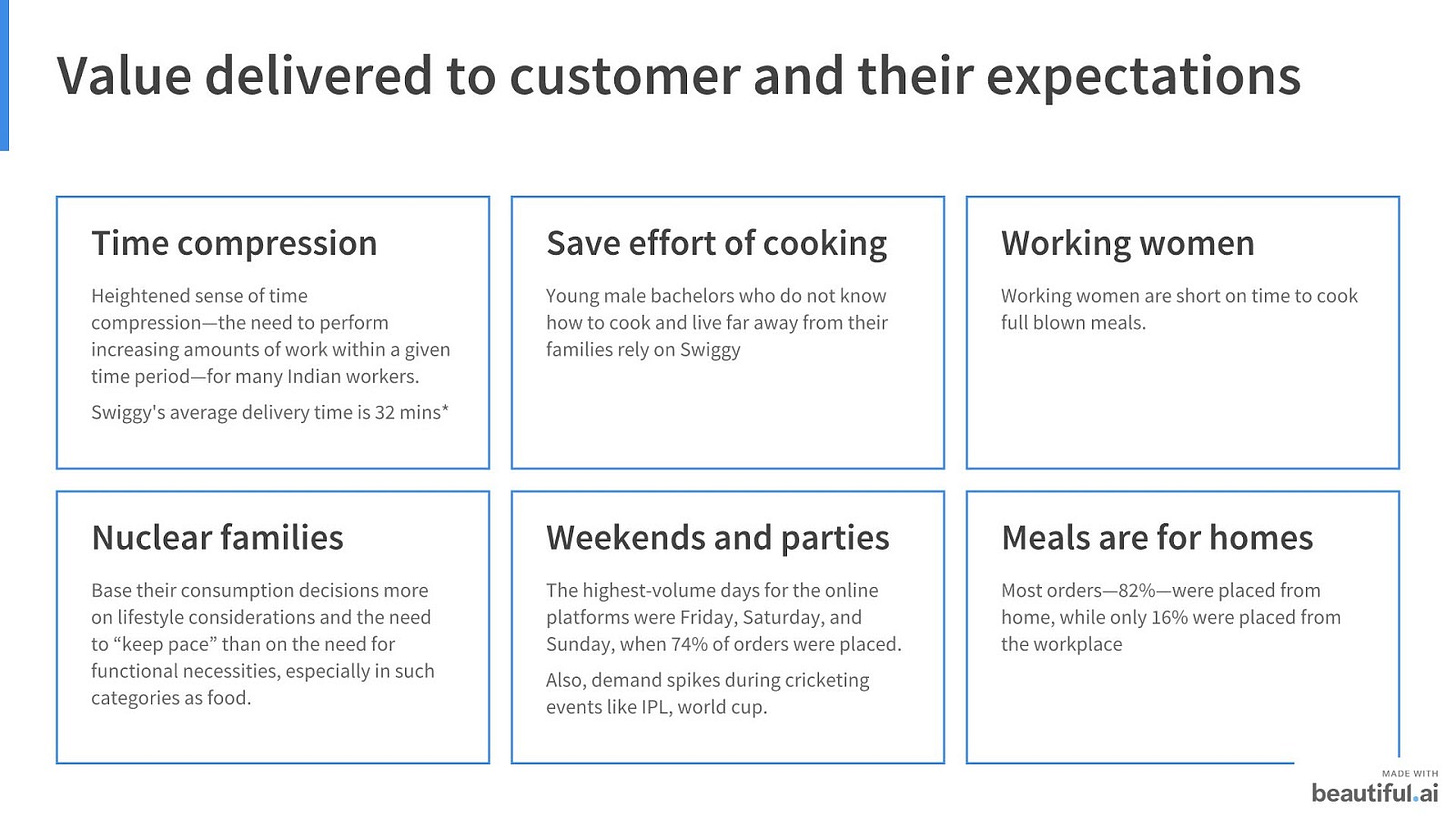

There’s a wave of Indian users transacting online for the first time, using ride-sharing, food & grocery delivery, e-commerce, travel & hospitality, fintech, to access wider selection, get better prices (via sales/discounts), and experience convenience.

TAM for online food delivery in India was $4 billion in 2019 and is expected to grow to $8 billion in 2022, growing at a rate of 25% per year. To investigate where is this growth stemming from, here are a few indicators I think are worth looking at:

Online buyer base and spending expected to increase from $40 billion (2020) to $130 billion (2025). The average online spend/buyer is set to become 2.15X from $20/year currently to ~$43/year in only 5 years. At the heart of this lies:

(i) Increasing smartphone penetration: smartphones in India will double in the next 3 years to ~700 million,

(ii) Rise of young and tech-savvy users with more disposable income, and

(iii) Growing trust and convenience of online services amongst Indians.

While the online spend would increase to $130 billion, it would still be ~6% of the total spend (i.e. 90+% of commerce would remain offline)

India is all set to become the middle-class economy and consumer spending is set to rise from $1.5 trillion to $6 trillion in 10 years.

(i) 140 million new upper-middle and high-income households will emerge. This section spends between 12% to 35% of their income on F&B and thus, with an increase in avg disposable income, $ spent on food is bound to rise.

(ii) By 2030, 77% (1.15 billion) of India’s population will be Millenials and Generation-Z. These people will depend on online services and in turn influence the behavior in their respective households.

(iii) 90 million nuclear households headed by young, tech-savvy decision-makers who are aspirational, short on time and prefer convenience. These households typically spend 20-30% more per capita than joint families.

Food tech user base reach has been growing at a whopping rate of more than 150%.

(i) Indian food-tech startups have raised $2.5 billion with online food delivery raising $2.1 billion alone — enabling expansion of operations to ~500 cities.

(ii) Spend on online food service as % of total foodservice spend is fairly low at 4%, presenting a large opportunity for growth.

(iii) In the past 2 years, engagement on food delivery apps has increased from 32 mins/month to 72 mins/month.

(*this is a two-edged metric; more engagement time means more orders/month; more engagement time also means more confusion due to paradox of choice)

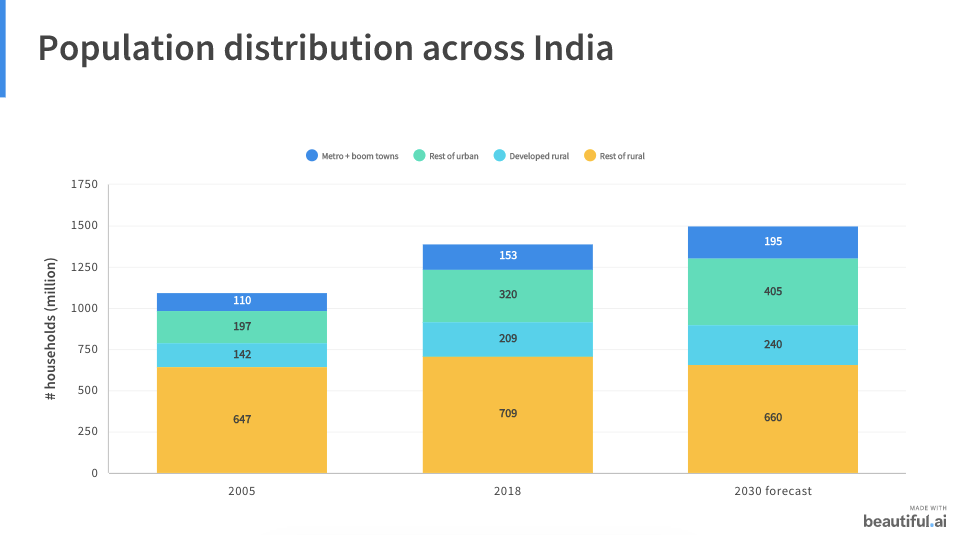

While metro cities have been driving the demand traditionally, the non-metro cities have started to acquire a taste for online food ordering.

(i) In 2019, food delivery in non-metro cities grew 7X faster compared to metro cities (80% vs 12%).

(ii) 60% (900 million) of households will reside in small, rural towns, and ~55% ($3.3 trillion) spending will come from these households.

Urge to order (and reorder)

While the macro trends look favorable, the real picture isn’t all that rosy.

There is good and bad news in this graph. The good news is that Swiggy’s # daily orders doubled from 700K to 1.4 million in 1 year, but the sobering companion finding is that the AOV is decreasing. Boiled down to basics, it means:

Growth is at least partially driven by existing users using more of the service, albeit for smaller orders.

It could also reflect that the new orders are coming from parts of the country where food is cheaper.

Another reason for this could be the introduction of Swiggy Pop — a low cost, single-serve meal with no delivery charge.

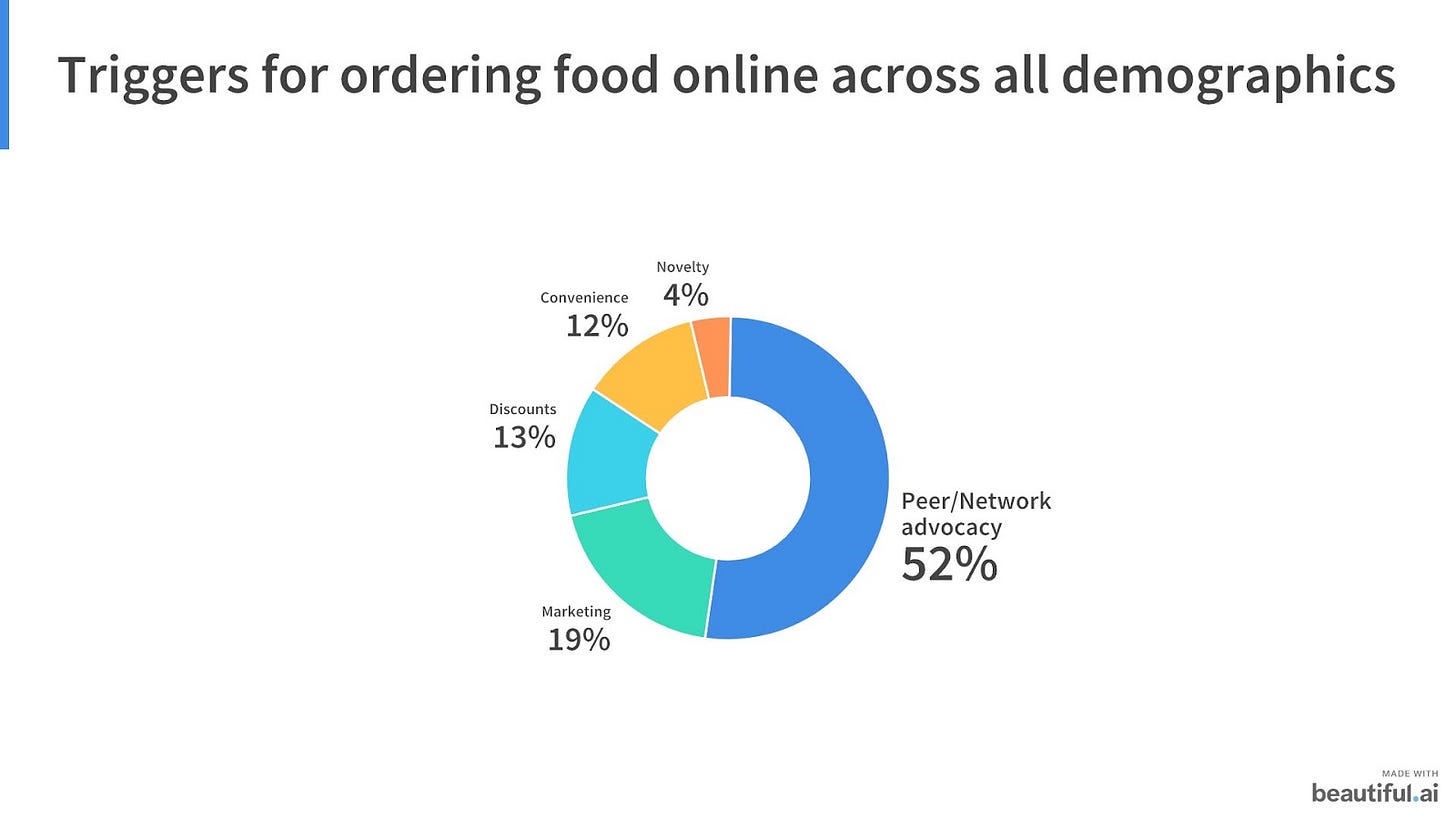

To decode the growth in # daily orders and understand the triggers of ordering food online (adoption and retention), it is important to answer:

What are the drivers for adoption?

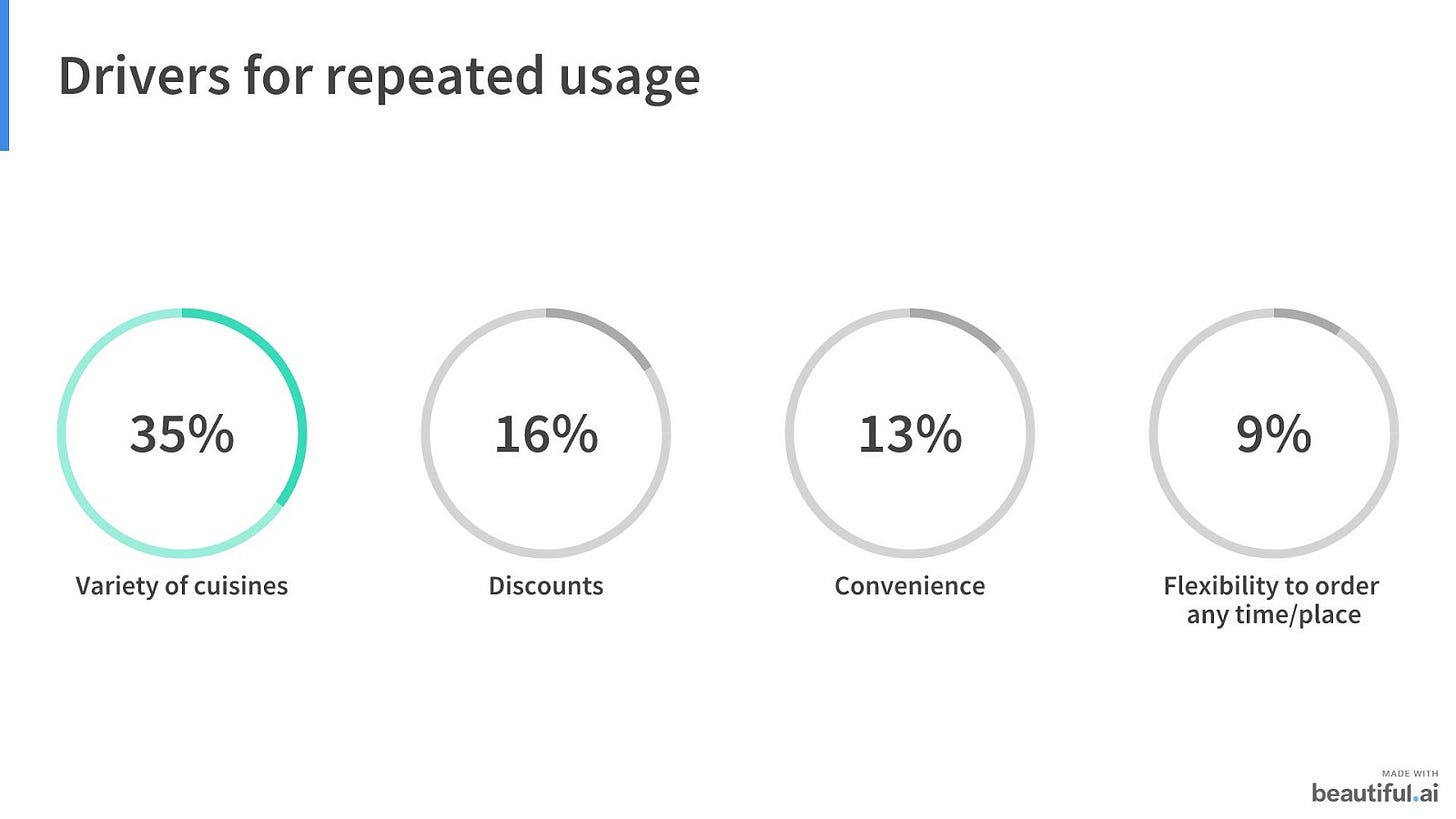

What drives continued usage across users?

What value are people deriving and what are their expectations from Swiggy?

What are the barriers for people to use Swiggy?

52% peer or network advocacy as the primary trigger for adoption means:

Existing users are attracting more users.

The LTV for existing users is high (and order frequency is good).

It indicates that Swiggy’s services are valuable to existing users (wide selection of restaurants/cuisines, UX, etc.). It also means that Swiggy would have to spend less to retain these users and can spend more $ acquiring new users.

To ensure repeat usage, Swiggy needs to keep expanding and innovating its partnerships with restaurants to offer a wider selection. It also makes a case for Swiggy to further expand its cloud kitchen business (lower cost structure, a storehouse for variety, ensuring timeliness).

In addition to customer archetypes mentioned above, another profile Swiggy can target is the health-conscious individual (Eat.fit’s target base). These individuals are looking for healthy dishes, delivered to them daily (preferably on subscription), and customized to their nutritional requirements.

Barriers for adoption

Trust & reliability: First time users have a hard time trusting the platform since it's not performing the core service (food preparation). Users have questions like what if things go wrong, who takes responsibility?

Food quality concerns: Over quality of ingredients used, packaging, taste, and hygiene. This might become a bigger concern due to the Coronavirus situation.

Delivery charges: Customers are uncomfortable paying delivery charges for restaurants in the vicinity and find it unfairly high.

Customization/personalization: Although Swiggy offers some customizability (cooking instructions), users aspire to a deeper level of personalization (meals delivered at the scheduled time, prepared according to their taste/preference).

Growth at all costs

Swiggy has shown immense user growth potential (and so has its competition). But this growth has come at a significant cost.

The troubling feature of Swiggy is that its losses are getting worse y-o-y not only in absolute $’s, but also as % of revenue. In 2019, Swiggy had to spend $3.24 to earn $1 of revenue.

Here’s how Swiggy’s financial metrics compared to Zomato in the past year.

Note: Some of the figures are estimates due to the non-availability of data.

In FY19, Swiggy made a loss of $376 million on revenue of $143 million, a negative 263% margin. Another point to note is that Swiggy’s fixed costs are low (26.9%) vs variable costs (73.1%). This is worrisome because when economies of scale kick in, fixed cost/unit sales go down but the variable costs will rise to serve more orders.

On the other hand, Zomato in recent filings said it has cut its burn by 50% to $15-20 million/month (annualized to $180-$240 million).

To have a clear path to profitability and building a sustainable business, Swiggy should not only look at diversifying its revenue streams (cloud kitchens, Swiggy Super, Swiggy Go, and Swiggy Stores), it also needs to find a way to reduce its costs.

Lower discounts → lower marketing expenses + CAC, introduce variable pricing.

Lower delivery costs → limited menu and slotted delivery time to lower the uncertainty of orders, consider futuristic alternatives like drones.

Leaner org structure: Zomato has 5000 corporate employees vs Swiggy which has 8000 corporate employees.

Business equation and growth levers

While currently unprofitable, the food delivery business would be similar to other delivery businesses (e.g., e-commerce, grocery), and aspires to be profitable over time through greater aggregation of orders and operational scale. I’ve put together equations for different revenue streams to test assumptions and pinpoint the high growth levers. I also tried to assess how operational scale will influence costs and profitability.

Business equations

Revenue/order = (AOV * Take rate %) + (Delivery revenue)

Variable costs/order = Delivery costs + Packaging costs + Processing costs

Contribution margin I = # Orders * (Revenue/order - Variable costs/order)

Contribution margin I (%) = Contribution margin/Revenue

Operational equations

Order arrival rate per hour = #Orders/(365*24)

Average service time per order = Prep time + Delivery time

1 / Average service time per order = Deliveries completed per hour

#Orders / Deliveries completed per hour = #DPs

#DPs * Multiplier (assuming 1.5X for unpredictable demand) = #DPs employed

Multiplier ∝ 1/Mean waiting time for a customer

(DP = Delivery partner)

Cost of convenience

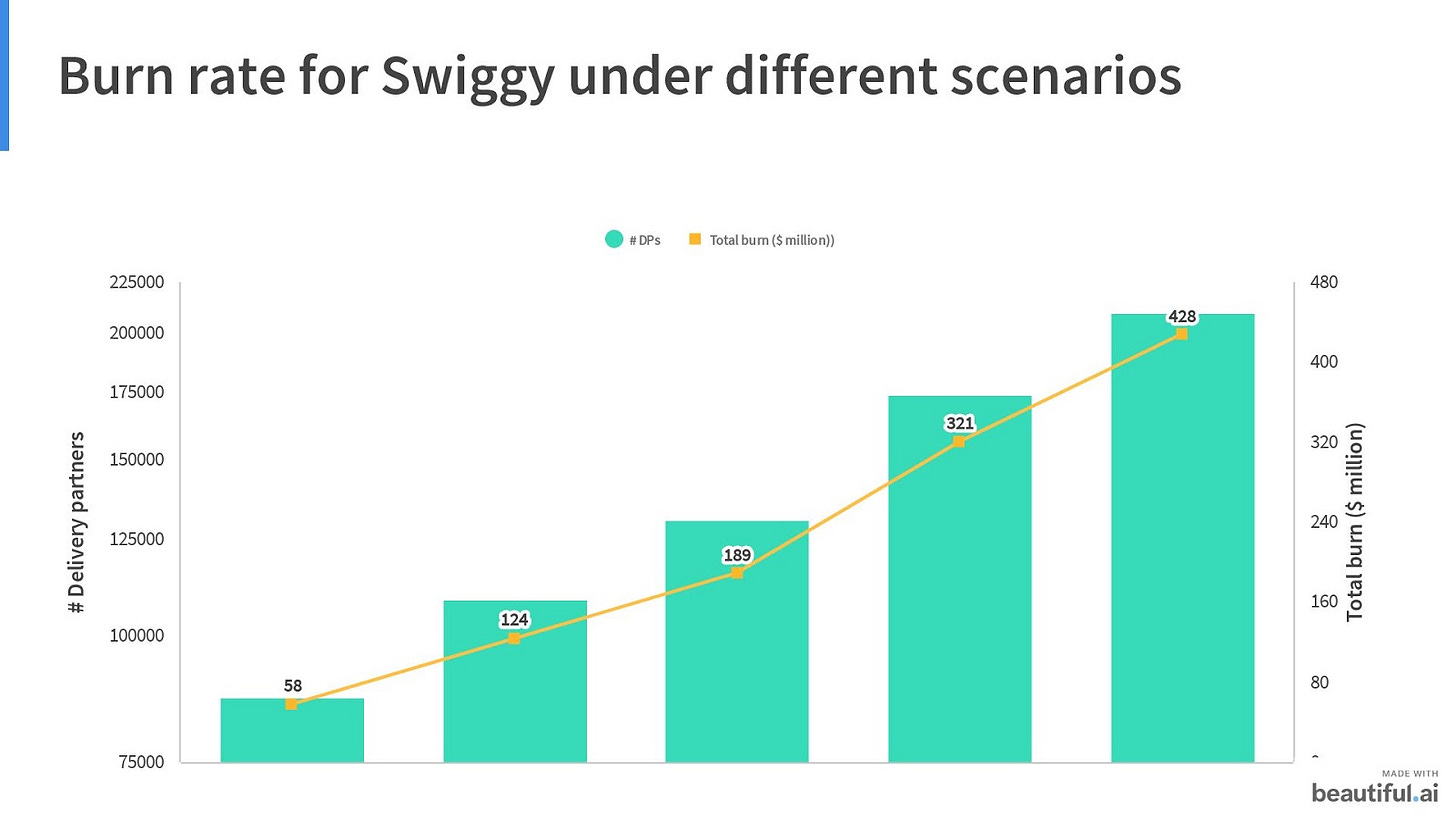

The following data illustrates the relationship between costs incurred because of # DPs, minimum AOV to attain profitability, and burn rate in different scenarios.

Note:

Assuming 1.4 million orders/day → 58K orders/hour; average time taken to complete 1 order = 30 mins; 1 DP completes 2 orders/hour (100% utilization).

Foodtech companies earn ~20% commission from restaurants and 5% from customers on $4 AOV. The cost of delivery is $0.7, leaving a $0.3 or 7% operating margin for the company.

Breakeven AOV for 210K delivery partners is $17.69 (4X the current AOV). A typical order in the US is $20-$30 but you can’t expect that in India. Also, as the # delivery partners increase, the burn rate becomes unsustainable, leaving high odds for unprofitability.

The demand pattern of orders is unpredictable with concentrated peaks around mealtimes. Also, the external factors such as traffic, weather, kitchen ops are beyond anyone’s control. This creates a need for a higher multiplier to reduce ETA and thus, more DPs. With more DPs on payroll, Swiggy needs to keep them occupied during non-peak hours (the idea behind Swiggy Go, Swiggy Stores). Models that Swiggy can adopt to tackle unpredictability and externalities:

(i) Subscription-based slotted meal deliveries, (ii) Cloud kitchens

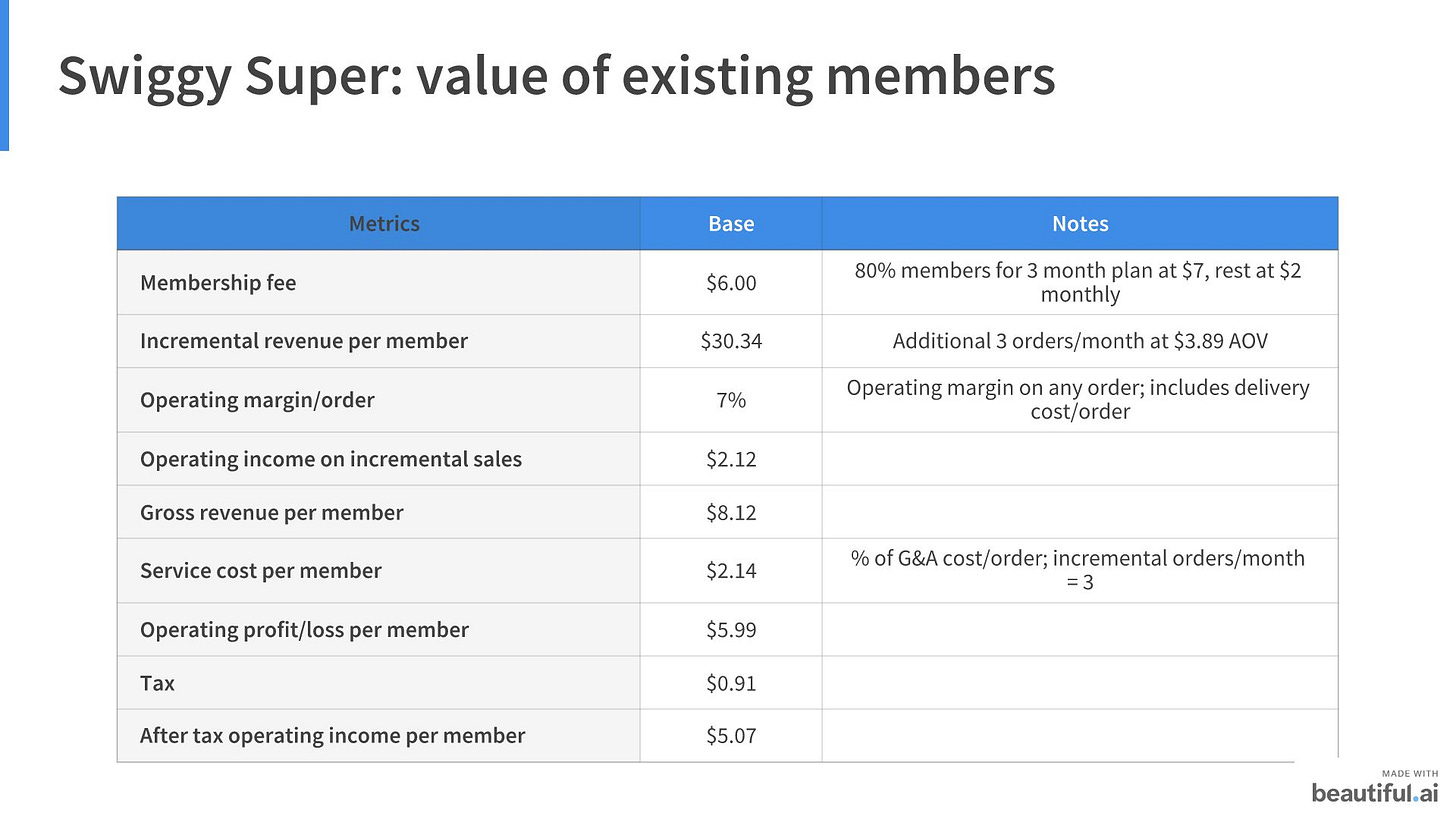

Swiggy Super

A hybrid revenue model (subscription + transactional, like Amazon Prime), it improves stickiness, makes revenue more predictable + encourages more transactions to take place. Here’s a simple economic analysis of Super memberships:

Hybrid revenue models are better because:

Purely subscription models alone have low upside potential (can’t increase the fee by much).

Standalone transactional models are risky because of uncertainty (whether the user will come back and make a purchase or not).

Cloud kitchens

Swiggy is a demand aggregator. It has data on what people want to eat, at what hour, where they stay, and what price works for them. This paves way for Swiggy to go the Netflix route, go a step beyond aggregating demand & distributing supply, and become a producer itself. The cloud kitchens are a storehouse for variety, can deliver faster, and most importantly, have better contribution margins (see below).

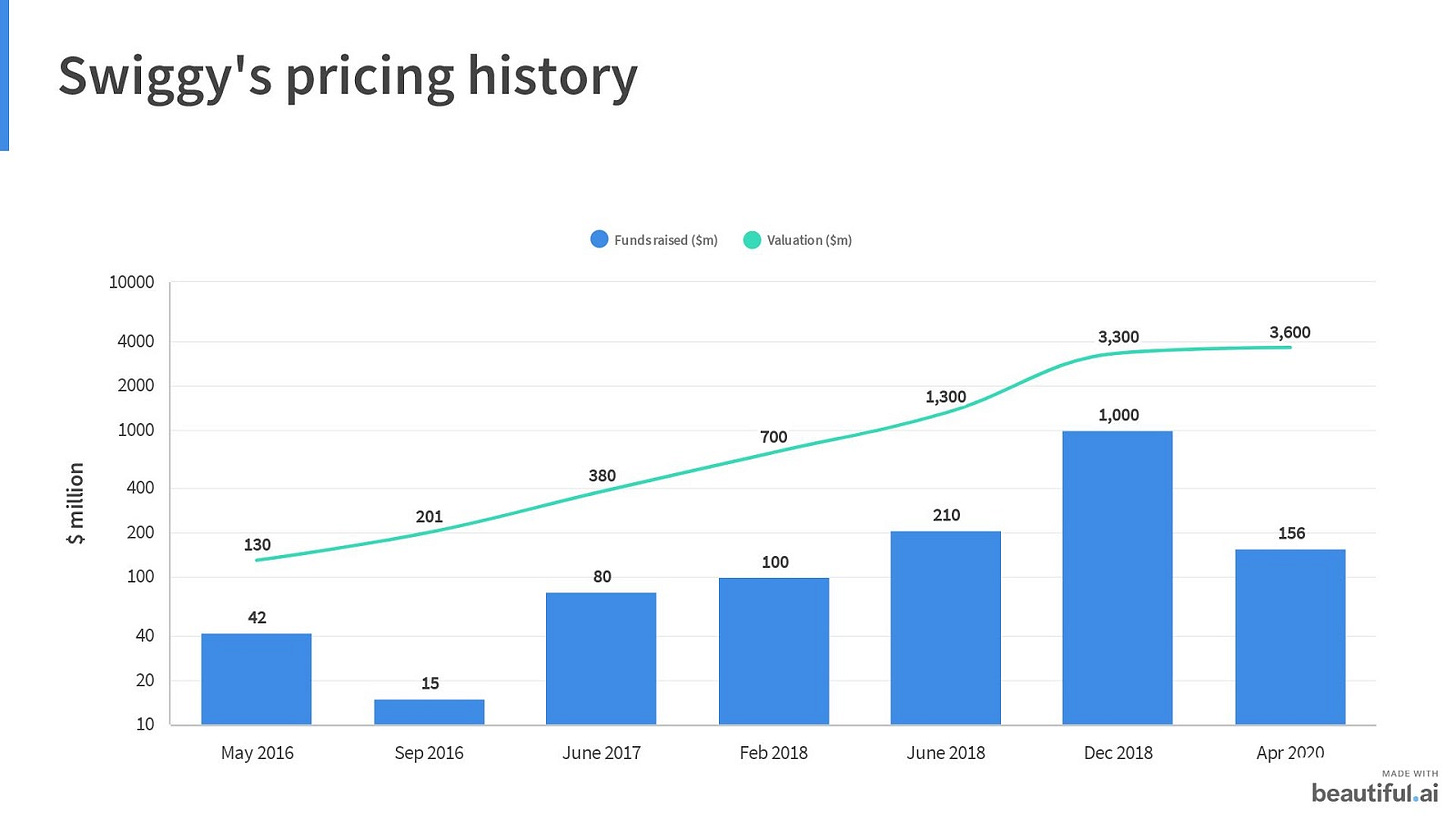

How VCs look at Swiggy

The high growth numbers are flattering, being the primary reason why Swiggy has been successful in raising $1.6 billion from VCs.

VCs have consistently “priced” Swiggy like a user-based company (like Netflix, Spotify) based on # users and # daily orders. This might backfire because:

Swiggy is a logistics company, not a user-based one.

Swiggy’s variable costs (discounts + CAC) remain extremely high which is unsustainable for transactional business models.

Swiggy’s spending more money servicing existing users vs acquiring new ones.

My take: User-based firms collect exclusive data from their users that they use to generate revenue, have significant economies of scale, and network effects.

Network effects

I think that while there are network effects in food delivery, they are not very strong. The network effects are:

# customers grow → # restaurants grow → selection/variety grows → the value to the user grows (plateaus because there are only so many restaurants/cuisines + restaurants are incentivized to be present on all platforms thus it’s harder for a winner takes it all dynamic to emerge).

Low ETA for superior experience: This can only be optimized to fall to a certain point. The delivery person acquisition has made the network effect a little stronger. With multiple players, competitors have to keep sinking money into incentives for the driver side to maintain their market share.

In conclusion

While the online demand $ spent in India will be growing at a healthy pace (10%), the unit economics of operations-heavy, last-mile logistics companies in food delivery does not add up well. These companies have remained unprofitable for long and have accumulated unsustainable losses. They need to reduce discounts and find ways to cut costs. They also need to tweak their business model to adjust for risk, reduce uncertainties, and create a differentiated brand. Diversifying the business into adjacent categories might be a relevant strategy. Will these companies get acquired or become big enough to go public, only time will tell.

Bottom line: Last-mile logistics is an operations-heavy, low-margin business. In the long run, I don't see how the market can sustain so many parallel micro-logistics networks and Swiggy needs to differentiate itself.